The humanitarian sector, particularly the field of global health, is rich with data. The appetite for global health and humanitarian data has grown exponentially with the introduction of digital tools. NGOs regularly report big data numbers about the millions of people in their catchment populations, the hundreds of thousands of treatments provided or children educated, and the tens of thousands of deliveries assisted by a skilled birth attendant. If you work in this field, you likely have at least 10 Excel spreadsheets open on your laptop right now.

But how much of that big data is actually helping us do better?

The answer to that question can be found in an assessment of where those big numbers originate. Behind every big number is a lot of little numbers, collected by people tasked with recording a simple interaction with a patient, a student, a community member, or a survivor. Donors, government ministries, agencies and academic partners regularly cascade requests for data that multiply and complicate the simple interaction into a complex, and often redundant, set of data requirements for the same singular interaction. The reality is that the resources, operations, quality, and overall impact of any organization rely on those recorded interactions.

Unfortunately, the widely held appetite for those numbers is not matched with considerations to ensure that they are properly funded or structured. In conflict-affected contexts, efforts to respond with quality data are often hampered by limited resources and numerous uncoordinated requirements from donors.

On a field visit to Cote d’Ivorie, I found that the required data collection for health facilities included 1,200 data elements every week, requiring 12 hours of data entry per week. That is 12 hours of data entry for one health facility for one project by a single person.

Ensuring a reasonable level of quality from a data collector completing hundreds of data entries on multiple forms needs guidance, supervision, and support. The limited resources attributed to measurement and monitoring means that support is — in this case and many others — unavailable.

Quality data relies not just on quality collection, but also on support to effectively monitor and evaluate the collected data. However, the real-world scenario surrounding data requirements is a single health manager expected to monitor the performance of one health facility for the 1,200 data elements being collected. The collection will have then produced masses of data that has become noise, instead of the primary tool used to make sound and effective decisions.

Quality measurement is vital and must be considered critical by humanitarian and development actors. It is the blood flow through the living system. For NGOs and ministries, data is the most strategic asset.

We can’t continue responding to the high demand for data without acknowledging the limited resources available to ensure its quality. One potential opportunity for improvement is to allocate appropriate resources to monitoring and evaluation. Currently, within a standard project budget, monitoring and evaluation commonly falls between 5 to 10 percent of total budget costs.

But there are two approaches that can practically help us produce meaningful data that results in better service delivery. The first solution is pragmatic: Collect less. Do more.

For example, at any given time, I generally know how much I have in my bank account and monitor that amount. I do not know specifically the payments flowing toward utilities, rent, or Netflix, but I do know when the account level dips too low and how to identify and investigate the cause.

In a similar way, the selection and monitoring of only essential indicators can help us collect less and do more. Often, the masses of data collected that are of questionable quality are simply adding noise and confusion, rather than telling any meaningful story. Organizations, as well as those accessing services and the project donors, would be better served by collecting fewer indicators of good quality rather than 70 indicators of questionable quality. Taking this approach of fewer indicators would simplify training for staff on analysis and action. In return, we would need to make a coordinated effort to educate donors and ministries about the best use of resources for data monitoring.

The second solution is the correct introduction and implementation of technology. Globally, I believe the best use of technology to improve people’s health status is not a cutting-edge diagnostic tool or an integrated collection of satellites. The best use of technology would be the implementation of person-level digital information systems that accurately reflect the daily activities of care providers and provide a real-time system for collection, analysis, and feedback.

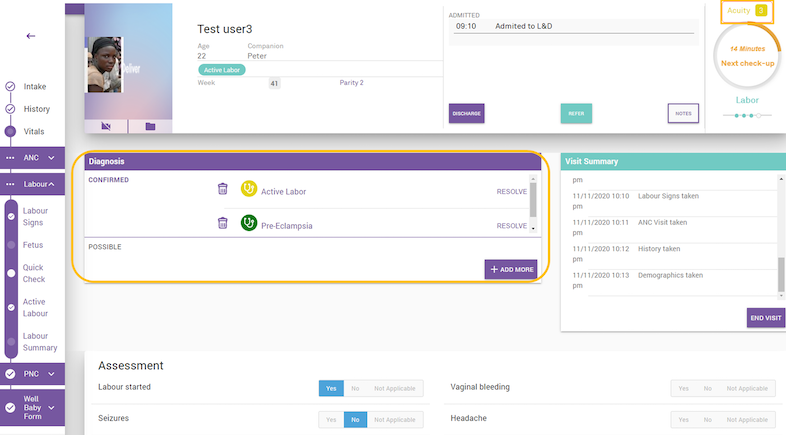

A user is guided through a patient assessment and provided with real-time possible diagnosis and treatment plans. An acuity score, a metric based on presenting signs and symptoms, is also calculated in real-time to allow a care provider to identify the most severe patients for quicker treatment.

At VecnaCares, our philosophy is that, at its core, an information system, no matter how technologically advanced, is simply a tool to record every encounter a person has with that system: every check-up, every class attended, every prescription, every bed net distributed.

With the global surge of tablets, smartphones, and laptops, it is now possible to accurately collect the key building block of any information system – source data at the individual level. For health information systems specifically, if patient-level data can be accurately collected and structured, information can be fed throughout the data flow. The result is a better allocation of resources, better understanding of population health, and better health decisions for patients – all from accurate digital person-level data management.

One particular project at VecnaCares, Project iDeliver, is an example of a technology solution having an impact across a health system – from patients to providers to ministry stakeholders. iDeliver, which has been developed and implemented for over 16,000 births in three countries, is an advanced clinical decision support tool to collect patient-level information at any point in a woman’s pregnancy. The open-source application will support the diagnosis and treatment of pregnancy complications, in real-time. The user interface and feature set were developed through a series of human-centered design workshops in low-resource settings to develop an application that mimics the daily activities of a care provider, rather than a more structured application which might be just another technology-based burden on the already overworked staff. The patient-level data is organized, aggregated and prioritized to support healthcare staff to focus on the most severe patients, resulting in improved health outcomes.

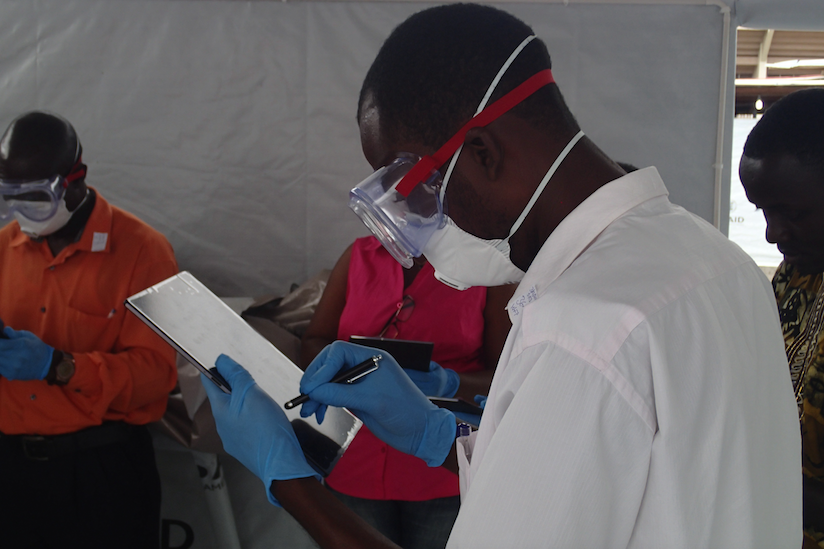

A care provider is trained to use electronic medical records during the Ebola outbreak in Liberia.

Similarly, during this time of global pandemic, digitally collecting patient screening and diagnosis data would allow the possibility of quickly identifying concentrated COVID-19 outbreaks and potentially allow for more targeted restrictions based on real-time prevalence.

By examining information systems holistically with a focus on the source data collection, all of the necessary factors for success are in play, but it has required a significant investment in those pieces combined with a commitment for more mindful data collection and the discretionary approach for technology implementation.

Across the global health and the aid community, there should be a renewed focus on the singular activity that allows the industry to exist – the measurement of one client encounter. Our decisions of what that information is and how it is collected might be the most critical and fundamental decisions throughout any project.

About The Author

Paul Amendola, MPH is the Executive Director of VecnaCares. His work specializes in using digital data system for measurement, increasing data quality, and methodology for successful technology deployments in low-resource settings. He has worked with over 30 national health systems over his twelve year career and has previously had positions various NGOs including the International Rescue Committee and The Millennium Villages Project.